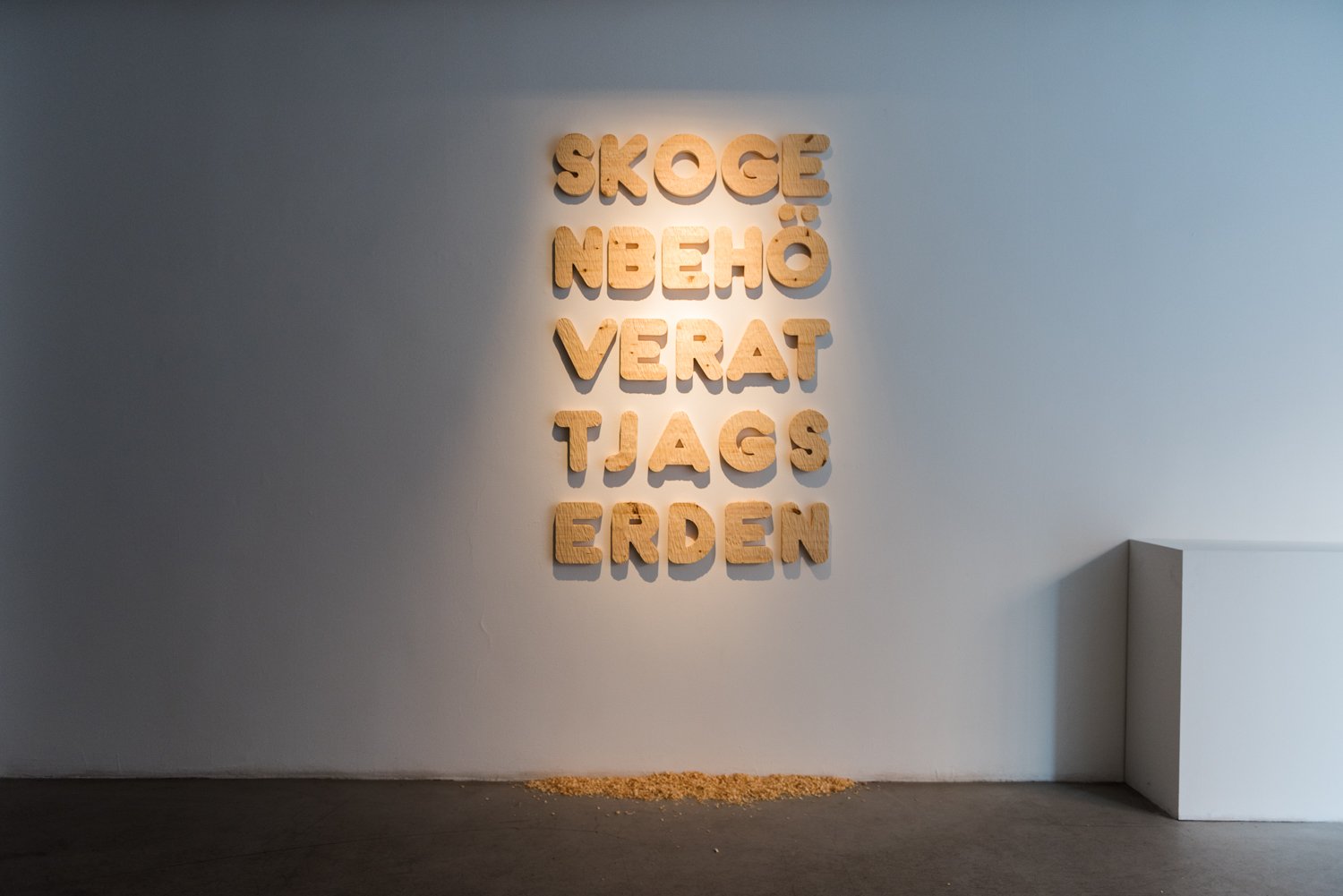

Skogen behöver att jag ser den

Solo exhibition at NUA Gallery 2016, Galleri Verkligheten 2017, and Eberlingmuseet 2017

Animals in or out of sync with the surrounding nature reoccurs in Magnusson’s video works, which portrays something highly human. In the newly produced Nattskärran (2016) she is looking for a bird that, 30 years ago, left the area where her family has lived for generations. Old folklore says that the European nightjar was a harbor for dead people’s souls and, like other nocturnal birds, was associated with dark powers. The bird becomes a symbol of our inner darkness and urges us to embrace our shadow.

In the video Magnusson collects feathers hoping for it to be feathers from the nightjar, in a desire to seek and meet what really hurts. The feathers later forms the mirrored forest views that Magnusson also presents in the exhibition. If landscape paintings are a kind of spaced studies of the surroundings Magnusson’s collages are rather described as portraits, simply because the forest is a friend which the artist examines and reasons with.

Magnusson’s sculptures are often similar to disproportionate bird nests or unidentifiable dens made out of natural materials. With the bird as a symbol of freedom, a creature which you have to handle carefully if you want it to stay, her nests become a metaphor for both independence as much as belonging.

There is a continuous string of criticism in Magnusson’s work where personal experiences meet irritating norms. In the exhibition Skogen behöver att jag ser den Magnusson invit us to wanderings. She refers to Tomas Tranströmers thoughts about what happens to people who dare to deviate from the trodden path. “There are, deep in the woods, an unexpected glade that can only be found by those who have gone astray”.

Magnusson uncovers the inner conflict that characterizes people who feel demanded to question the habitual behavior. Parallel with the responsibility to disbelieve the power and habitual patterns, which only favors the strongest, the thought of inner peace also seems tempting. With such a complex attitude towards existence it is consoling that the roving beingness offers a special reward. The feminist writer and historian Rebecca Solnit has also praised aimless detours, amongst others in “A field guide to getting lost”. Through this collection of cultural studies she uses the metaphor of getting lost to explain different life experiences and phenomenons of our time. Both Solnit and Magnusson view art as a place for aimless wandering, a forest you bravely enters without knowing if or how you will get out.

– Susanne Ewerlöf, freelancing curator

Video stills from Nattskärran, 12 min